-->

No, @Junior, I press add Mac, type IP, username and password, wait while it checks Mono and Xamarin.iOS on the Mac, then it fails to install the Broker. – matt.dolfin Dec 25 '20 at 3:40 Okey, then you could have a check whether the version of VisualStudio and Xcode is the latest version. Building apps with Xamarin.Mac is a great way to build powerful apps for macOS that harness the power of C#. In this blog post, we created a basic Pomodoro timer application for macOS. If you want to learn more about Xamarin.Mac, check out the Xamarin.Mac documentation and get involved in discussions on the forum! This manifests in which IDE you use whether Visual Studio 2019, Visual Studio for Mac, or even Visual Studio Code.NET MAUI will be available in all of those, and support both the existing MVVM and XAML patterns as well as future capabilities like Model-View-Update (MVU) with C#, or even Blazor.

Xamarin.Mac allows for the development of fully native Mac apps in C# and .NET using the same macOS APIs that are used when developing in Objective-C or Swift. Because Xamarin.Mac integrates directly with Xcode, the developer can use Xcode's Interface Builder to create an app's user interfaces (or optionally create them directly in C# code).

Additionally, since Xamarin.Mac applications are written in C# and .NET, code can be shared with Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android mobile apps; all while delivering a native experience on each platform.

This article will introduce the key concepts needed to create a Mac app using Xamarin.Mac, Visual Studio for Mac and Xcode's Interface Builder by walking through the process of building a simple Hello, Mac app that counts the number of times a button has been clicked:

The following concepts will be covered:

- Visual Studio for Mac – Introduction to the Visual Studio for Mac and how to create Xamarin.Mac applications with it.

- Anatomy of a Xamarin.Mac Application – What a Xamarin.Mac application consists of.

- Xcode's Interface Builder – How to use Xcode's Interface Builder to define an app's user interface.

- Outlets and Actions – How to use Outlets and Actions to wire up controls in the user interface.

- Deployment/Testing – How to run and test a Xamarin.Mac app.

Requirements

Xamarin.Mac application development requires:

- A Mac computer running macOS High Sierra (10.13) or higher.

- Xcode 10 or higher.

- The latest version of Xamarin.Mac and Visual Studio for Mac.

To run an application built with Xamarin.Mac, you will need:

- A Mac computer running macOS 10.7 or greater.

Warning

The upcoming Xamarin.Mac 4.8 release will only support macOS 10.9 or higher.Previous versions of Xamarin.Mac supported macOS 10.7 or higher, butthese older macOS versions lack sufficient TLS infrastructure to supportTLS 1.2. To target macOS 10.7 or macOS 10.8, use Xamarin.Mac 4.6 orearlier.

Starting a new Xamarin.Mac App in Visual Studio for Mac

As stated above, this guide will walk through the steps to create a Mac app called Hello_Mac that adds a single button and label to the main window. When the button is clicked, the label will display the number of times it has been clicked.

To get started, do the following steps:

Start Visual Studio for Mac:

Click on the New Project.. button to open the New Project dialog box, then select Mac > App > Cocoa App and click the Next button:

Enter

Hello_Macfor the App Name, and keep everything else as default. Click Next:Confirm the location of the new project on your computer:

Click the Create button.

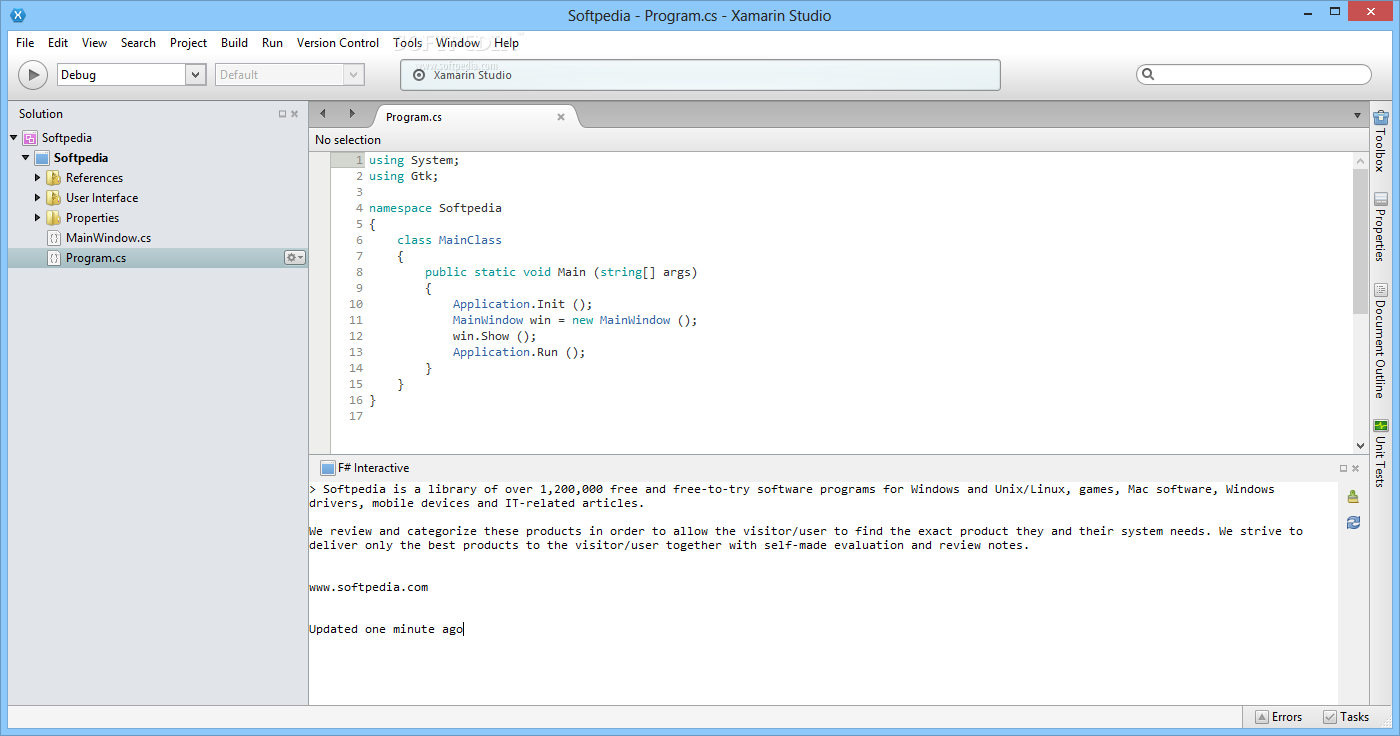

Visual Studio for Mac will create the new Xamarin.Mac app and display the default files that get added to the app's solution:

Visual Studio for Mac uses the same Solution and Project structure as Visual Studio 2019. A solution is a container that can hold one or more projects; projects can include applications, supporting libraries, test applications, etc. The File > New Project template creates a solution and an application project automatically.

Anatomy of a Xamarin.Mac Application

Xamarin.Mac application programming is very similar to working with Xamarin.iOS. iOS uses the CocoaTouch framework, which is a slimmed-down version of Cocoa, used by Mac.

Take a look at the files in the project:

- Main.cs contains the main entry point of the app. When the app is launched, the

Mainclass contains the very first method that is run. - AppDelegate.cs contains the

AppDelegateclass that is responsible for listening to events from the operating system. - Info.plist contains app properties such as the application name, icons, etc.

- Entitlements.plist contains the entitlements for the app and allows access to things such as Sandboxing and iCloud support.

- Main.storyboard defines the user interface (Windows and Menus) for an app and lays out the interconnections between Windows via Segues. Storyboards are XML files that contain the definition of views (user interface elements). This file can be created and maintained by Interface Builder inside of Xcode.

- ViewController.cs is the controller for the main window. Controllers will be covered in detail in another article, but for now, a controller can be thought of the main engine of any particular view.

- ViewController.designer.cs contains plumbing code that helps integrate with the main screen's user interface.

The following sections, will take a quick look through some of these files. Later, they will be explored in more detail, but it's a good idea to understand their basics now.

Main.cs

The Main.cs file is very simple. It contains a static Main method which creates a new Xamarin.Mac app instance and passes the name of the class that will handle OS events, which in this case is the AppDelegate class:

AppDelegate.cs

The AppDelegate.cs file contains an AppDelegate class, which is responsible for creating windows and listening to OS events:

This code is probably unfamiliar unless the developer has built an iOS app before, but it's fairly simple.

The DidFinishLaunching method runs after the app has been instantiated, and it's responsible for actually creating the app's window and beginning the process of displaying the view in it.

The WillTerminate method will be called when the user or the system has instantiated a shutdown of the app. The developer should use this method to finalize the app before it quits (such as saving user preferences or window size and location).

ViewController.cs

Cocoa (and by derivation, CocoaTouch) uses what's known as the Model View Controller (MVC) pattern. The ViewController declaration represents the object that controls the actual app window. Generally, for every window created (and for many other things within windows), there is a controller, which is responsible for the window's lifecycle, such as showing it, adding new views (controls) to it, etc.

The ViewController class is the main window's controller. The controller is responsible for the life cycle of the main window. This will be examined in detail later, for now take a quick look at it:

ViewController.Designer.cs

Xamarin Ide Mac Os

The designer file for the Main Window class is initially empty, but it will be automatically populated by Visual Studio for Mac as the user interface is created with Xcode Interface Builder:

Designer files should not be edited directly, as they're automatically managed by Visual Studio for Mac to provide the plumbing code that allows access to controls that have been added to any window or view in the app.

With the Xamarin.Mac app project created and a basic understanding of its components, switch to Xcode to create the user interface using Interface Builder.

Info.plist

The Info.plist file contains information about the Xamarin.Mac app such as its Name and Bundle Identifier:

It also defines the Storyboard that will be used to display the user interface for the Xamarin.Mac app under the Main Interface dropdown. In example above, Main in the dropdown relates to the Main.storyboard in the project's source tree in the Solution Explorer. It also defines the app's icons by specifying the Asset Catalog that contains them (AppIcon in this case).

Entitlements.plist

The app's Entitlements.plist file controls entitlements that the Xamarin.Mac app has such as Sandboxing and iCloud:

For the Hello World example, no entitlements will be required. The next section shows how to use Xcode's Interface Builder to edit the Main.storyboard file and define the Xamarin.Mac app's UI.

Introduction to Xcode and Interface Builder

As part of Xcode, Apple has created a tool called Interface Builder, which allows a developer to create a user interface visually in a designer. Xamarin.Mac integrates fluently with Interface Builder, allowing UI to be created with the same tools as Objective-C users.

To get started, double-click the Main.storyboard file in the Solution Explorer to open it for editing in Xcode and Interface Builder:

This should launch Xcode and look like this screenshot:

Before starting to design the interface, take a quick overview of Xcode to orient with the main features that will be used.

Note

The developer doesn't have to use Xcode and Interface Builder to create the user interface for a Xamarin.Mac app, the UI can be created directly from C# code but that is beyond the scope of this article. For the sake of simplicity, it will be using Interface Builder to create the user interface throughout the rest of this tutorial.

Components of Xcode

When opening a .storyboard file in Xcode from Visual Studio for Mac, it opens with a Project Navigator on the left, the Interface Hierarchy and Interface Editor in the middle, and a Properties & Utilities section on the right:

The following sections take a look at what each of these Xcode features do and how to use them to create the interface for a Xamarin.Mac app.

Project Navigation

When opening a .storyboard file for editing in Xcode, Visual Studio for Mac creates a Xcode Project File in the background to communicate changes between itself and Xcode. Later, when the developer switches back to Visual Studio for Mac from Xcode, any changes made to this project are synchronized with the Xamarin.Mac project by Visual Studio for Mac.

The Project Navigation section allows the developer to navigate between all of the files that make up this shim Xcode project. Typically, they will only be interested in the .storyboard files in this list such as Main.storyboard.

Interface Hierarchy

The Interface Hierarchy section allows the developer to easily access several key properties of the user interface such as its Placeholders and main Window. This section can be used to access the individual elements (views) that make up the user interface and to adjust the way they are nested by dragging them around within the hierarchy.

Interface Editor

The Interface Editor section provides the surface on which the user interface is graphically laid out. Drag elements from the Library section of the Properties & Utilities section to create the design. As user interface elements (views) are added to the design surface, they will be added to the Interface Hierarchy section in the order that they appear in the Interface Editor.

Properties & Utilities

The Properties & Utilities section is divided into two main sections, Properties (also called Inspectors) and the Library:

Initially this section is almost empty, however if the developer selects an element in the Interface Editor or Interface Hierarchy, the Properties section will be populated with information about the given element and properties that they can adjust.

Within the Properties section, there are eight different Inspector Tabs, as shown in the following illustration:

Properties & Utility Types

From left-to-right, these tabs are:

- File Inspector – The File Inspector shows file information, such as the file name and location of the Xib file that is being edited.

- Quick Help – The Quick Help tab provides contextual help based on what is selected in Xcode.

- Identity Inspector – The Identity Inspector provides information about the selected control/view.

- Attributes Inspector – The Attributes Inspector allows the developer to customize various attributes of the selected control/view.

- Size Inspector – The Size Inspector allows the developer to control the size and resizing behavior of the selected control/view.

- Connections Inspector – The Connections Inspector shows the Outlet and Action connections of the selected controls. Outlets and Actions will be discussed in detail below.

- Bindings Inspector – The Bindings Inspector allows the developer to configure controls so that their values are automatically bound to data models.

- View Effects Inspector – The View Effects Inspector allows the developer to specify effects on the controls, such as animations.

Use the Library section to find controls and objects to place into the designer to graphically build the user interface:

Creating the Interface

With the basics of the Xcode IDE and Interface Builder covered, the developer can create the user interface for the main view.

Follow these steps to use Interface Builder:

In Xcode, drag a Push Button from the Library Section:

Drop the button onto the View (under the Window Controller) in the Interface Editor:

Click on the Title property in the Attribute Inspector and change the button's title to Click Me:

Drag a Label from the Library Section:

Drop the label onto the Window beside the button in the Interface Editor:

Grab the right handle on the label and drag it until it is near the edge of the window:

Select the Button just added in the Interface Editor, and click the Constraints Editor icon at the bottom of the window:

At the top of the editor, click the Red I-Beams at the top and left. As the window is resized, this will keep the button in the same location at the top left corner of the screen.

Next, check the Height and Width boxes and use the default sizes. This keeps the button at the same size when the window resizes.

Click the Add 4 Constraints button to add the constraints and close the editor.

Select the label and click the Constraints Editor icon again:

By clicking Red I-Beams at the top, right and left of the Constraints Editor, tells the label to be stuck to its given X and Y locations and to grow and shrink as the window is resized in the running application.

Again, check the Height box and use the default size, then click the Add 4 Constraints Open dwg mac. button to add the constraints and close the editor.

Save the changes to the user interface.

While resizing and moving controls around, notice that Interface Builder gives helpful snap hints that are based on macOS Human Interface Guidelines. These guidelines will help the developer to create high quality apps that will have a familiar look and feel for Mac users.

Look in the Interface Hierarchy section to see how the layout and hierarchy of the elements that make up the user interface are shown:

From here the developer can select items to edit or drag to reorder UI elements if needed. For example, if a UI element was being covered by another element, they could drag it to the bottom of the list to make it the top-most item on the window.

With the user interface created, the developer will need to expose the UI items so that Xamarin.Mac can access and interact with them in C# code. The next section, Outlets and Actions, shows how to do this.

Outlets and Actions

So what are Outlets and Actions? In traditional .NET user interface programming, a control in the user interface is automatically exposed as a property when it's added. Things work differently in Mac, simply adding a control to a view doesn't make it accessible to code. The developer must explicitly expose the UI element to code. In order do this, Apple provides two options:

- Outlets – Outlets are analogous to properties. If the developer wires up a control to an Outlet, it's exposed to the code via a property, so they can do things like attach event handlers, call methods on it, etc.

- Actions – Actions are analogous to the command pattern in WPF. For example, when an Action is performed on a control, say a button click, the control will automatically call a method in the code. Actions are powerful and convenient because the developer can wire up many controls to the same Action.

In Xcode, Outlets and Actions are added directly in code via Control-dragging. More specifically, this means that to create an Outlet or Action, the developer will choose a control element to add an Outlet or Action to, hold down the Control key on the keyboard, and drag that control directly into the code.

For Xamarin.Mac developers, this means that the developer will drag into the Objective-C stub files that correspond to the C# file where they want to create the Outlet or Action. Visual Studio for Mac created a file called ViewController.h as part of the shim Xcode Project it generated to use Interface Builder:

Xamarin Demand

This stub .h file mirrors the ViewController.designer.cs that is automatically added to a Xamarin.Mac project when a new NSWindow is created. This file will be used to synchronize the changes made by Interface Builder and is where the Outlets and Actions are created so that UI elements are exposed to C# code.

Adding an Outlet

With a basic understanding of what Outlets and Actions are, create an Outlet to expose the Label created to our C# code.

Do the following:

In Xcode at the far right top-hand corner of the screen, click the Double Circle button to open the Assistant Editor:

The Xcode will switch to a split-view mode with the Interface Editor on one side and a Code Editor on the other.

Notice that Xcode has automatically picked the ViewController.m file in the Code Editor, which is incorrect. From the discussion on what Outlets and Actions are above, the developer will need to have the ViewController.h selected.

At the top of the Code Editor click on the Automatic Link and select the

ViewController.hfile:Xcode should now have the correct file selected:

The last step was very important!: if you didn't have the correct file selected, you won't be able to create Outlets and Actions, or they will be exposed to the wrong class in C#!

In the Interface Editor, hold down the Control key on the keyboard and click-drag the label created above onto the code editor just below the

@interface ViewController : NSViewController {}code:A dialog box will be displayed. Leave the Connection set to Outlet and enter

ClickedLabelfor the Name:Click the Connect button to create the Outlet:

Save the changes to the file.

Adding an Action

Next, expose the button to C# code. Just like the Label above, the developer could wire the button up to an Outlet. Since we only want to respond to the button being clicked, use an Action instead.

Do the following:

Ensure that Xcode is still in the Assistant Editor and the ViewController.h file is visible in the Code Editor.

In the Interface Editor, hold down the Control key on the keyboard and click-drag the button created above onto the code editor just below the

@property (assign) IBOutlet NSTextField *ClickedLabel;code:Change the Connection type to Action:

Enter

ClickedButtonas the Name:Click the Connect button to create Action:

Save the changes to the file.

With the user interface wired-up and exposed to C# code, switch back to Visual Studio for Mac and let it synchronize the changes made in Xcode and Interface Builder.

Note

It probably took a long time to create the user interface and Outlets and Actions for this first app, and it may seem like a lot of work, but a lot of new concepts were introduced and a lot of time was spent covering new ground. After practicing for a while and working with Interface Builder, this interface and all its Outlets and Actions can be created in just a minute or two.

Synchronizing Changes with Xcode

When the developer switches back to Visual Studio for Mac from Xcode, any changes that they have made in Xcode will automatically be synchronized with the Xamarin.Mac project.

Select the ViewController.designer.cs in the Solution Explorer to see how the Outlet and Action have been wired up in the C# code:

Notice how the two definitions in the ViewController.designer.cs file:

Line up with the definitions in the ViewController.h file in Xcode:

Visual Studio for Mac listens for changes to the .h file, and then automatically synchronizes those changes in the respective .designer.cs file to expose them to the app. Notice that ViewController.designer.cs is a partial class, so that Visual Studio for Mac doesn't have to modify ViewController.cs which would overwrite any changes that the developer has made to the class.

What mac do i have. Normally, the developer will never need to open the ViewController.designer.cs, it was presented here for educational purposes only.

Note

In most situations, Visual Studio for Mac will automatically see any changes made in Xcode and sync them to the Xamarin.Mac project. In the off occurrence that synchronization doesn't automatically happen, switch back to Xcode and then back to Visual Studio for Mac again. This will normally kick off a synchronization cycle.

Writing the Code

With the user interface created and its UI elements exposed to code via Outlets and Actions, we are finally ready to write the code to bring the program to life.

For this sample app, every time the first button is clicked, the label will be updated to show how many times the button has been clicked. To accomplish this, open the ViewController.cs file for editing by double-clicking it in the Solution Explorer:

First, create a class-level variable in the ViewController class to track the number of clicks that have happened. Edit the class definition and make it look like the following:

Next, in the same class (ViewController), override the ViewDidLoad method and add some code to set the initial message for the label:

Use ViewDidLoad, instead of another method such as Initialize, because ViewDidLoad is called after the OShas loaded and instantiated the user interface from the .storyboard file. If the developer tried to access the label control before the .storyboard file has been fully loaded and instantiated, they would get a NullReferenceException error because the label control would not exist yet.

Next, add the code to respond to the user clicking the button. Add the following partial method to the ViewController class:

This code attaches to the Action created in Xcode and Interface Builder and will be called any time the user clicks the button.

Testing the Application

It's time to build and run the app to make sure it runs as expected. The developer can build and run all in one step, or they can build it without running it.

Whenever an app is built, the developer can choose what kind of build they want:

- Debug – A debug build is compiled into an .app (application) file with a bunch of extra metadata that allows the developer to debug what's happening while the app is running.

- Release – A release build also creates an .app file, but it doesn't include debug information, so it's smaller and executes faster.

The developer can select the type of build from the Configuration Selector at the upper left-hand corner of the Visual Studio for Mac screen:

Building the Application

In the case of this example, we just want a debug build, so ensure that Debug is selected. Build the app first by either pressing ⌘B, or from the Build menu, choose Build All.

If there weren't any errors, a Build Succeeded message will be displayed in Visual Studio for Mac's status bar. If there were errors, review the project and make sure that the steps above have been followed correctly. Start by confirming that the code (both in Xcode and in Visual Studio for Mac) matches the code in the tutorial.

Running the Application

There are three ways to run the app:

- Press ⌘+Enter.

- From the Run menu, choose Debug.

- Click the Play button in the Visual Studio for Mac toolbar (just above the Solution Explorer).

The app will build (if it hasn't been built already), start in debug mode and display its main interface window:

If the button is clicked a few times, the label should be updated with the count:

Where to Next

With the basics of working with a Xamarin.Mac application down, take a look at the following documents to get a deeper understanding:

- Introduction to Storyboards - This article provides an introduction to working with Storyboards in a Xamarin.Mac app. It covers creating and maintaining the app's UI using storyboards and Xcode's Interface Builder.

- Windows - This article covers working with Windows and Panels in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Windows and Panels in Xcode and Interface builder, loading Windows and Panels from .xib files, using Windows and responding to Windows in C# code.

- Dialogs - This article covers working with Dialogs and Modal Windows in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Modal Windows in Xcode and Interface builder, working with standard dialogs, displaying and responding to Windows in C# code.

- Alerts - This article covers working with Alerts in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and displaying Alerts from C# code and responding to Alerts.

- Menus - Menus are used in various parts of a Mac application's user interface; from the application's main menu at the top of the screen to pop up and contextual menus that can appear anywhere in a window. Menus are an integral part of a Mac application's user experience. This article covers working with Cocoa Menus in a Xamarin.Mac application.

- Toolbars - This article covers working with Toolbars in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining. Toolbars in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Toolbar Items to code using Outlets and Actions, enabling and disabling Toolbar Items and finally responding to Toolbar Items in C# code.

- Table Views - This article covers working with Table Views in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Table Views in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Table View Items to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Table Items and finally responding to Table View Items in C# code.

- Outline Views - This article covers working with Outline Views in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Outline Views in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Outline View Items to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Outline Items and finally responding to Outline View Items in C# code.

- Source Lists - This article covers working with Source Lists in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Source Lists in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Source Lists Items to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Source List Items and finally responding to Source List Items in C# code.

- Collection Views - This article covers working with Collection Views in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Collection Views in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Collection View elements to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Collection Views and finally responding to Collection Views in C# code.

- Working with Images - This article covers working with Images and Icons in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining the images needed to create an app's Icon and using Images in both C# code and Xcode's Interface Builder.

The Mac Samples Gallery contains ready-to-use code examples to help learn Xamarin.Mac.

One complete Xamarin.Mac app that includes many of the features a user would expect to find in a typical Mac application is the SourceWriter Sample App. SourceWriter is a simple source code editor that provides support for code completion and simple syntax highlighting.

The SourceWriter code has been fully commented and, where available, links have been provided from key technologies or methods to relevant information in the Xamarin.Mac documentation.

Summary

This article covered the basics of a standard Xamarin.Mac app. It covered creating a new app in Visual Studio for Mac, designing the user interface in Xcode and Interface Builder, exposing UI elements to C# code using Outlets and Actions, adding code to work with the UI elements and finally, building and testing a Xamarin.Mac app.

Related Links

-->The Xamarin platform consists of a number of elements that allow you todevelop applications for iOS and Android:

- C# language – Allows you to use a familiar syntax and sophisticated features like Generics, LINQ and the Parallel Task Library.

- Mono .NET framework – Provides a cross-platform implementation of the extensive features in Microsoft's .NET framework.

- Compiler – Depending on the platform, produces a native app (eg. iOS) or an integrated .NET application and runtime (eg. Android). The compiler also performs many optimizations for mobile deployment such as linking away un-used code.

- IDE tools – The Visual Studio on Mac and Windows allows you to create, build, and deploy Xamarin projects.

In addition, because the underlying language is C# with the .NET framework,projects can be structured to share code that can also be deployed to WindowsPhone.

Under the Hood

Although Xamarin allows you to write apps in C#, and share the same codeacross multiple platforms, the actual implementation on each system is verydifferent.

Compilation

The C# source makes its way into a native app in very different ways on eachplatform:

- iOS – C# is ahead-of-time (AOT) compiled to ARM assembly language. The .NET framework is included, with unused classes being stripped out during linking to reduce the application size. Apple does not allow runtime code generation on iOS, so some language features are not available (see Xamarin.iOS Limitations ).

- Android – C# is compiled to IL and packaged with MonoVM + JIT'ing. Unused classes in the framework are stripped out during linking. The application runs side-by-side with Java/ART (Android runtime) and interacts with the native types via JNI (see Xamarin.Android Limitations ).

- Windows – C# is compiled to IL and executed by the built-in runtime, and does not require Xamarin tools. Designing Windows applications following Xamarin's guidance makes it simpler to re-use the code on iOS and Android.Note that the Universal Windows Platform also has a .NET Native option which behaves similarly to Xamarin.iOS' AOT compilation.

Visual Studio for Mac will create the new Xamarin.Mac app and display the default files that get added to the app's solution:

Visual Studio for Mac uses the same Solution and Project structure as Visual Studio 2019. A solution is a container that can hold one or more projects; projects can include applications, supporting libraries, test applications, etc. The File > New Project template creates a solution and an application project automatically.

Anatomy of a Xamarin.Mac Application

Xamarin.Mac application programming is very similar to working with Xamarin.iOS. iOS uses the CocoaTouch framework, which is a slimmed-down version of Cocoa, used by Mac.

Take a look at the files in the project:

- Main.cs contains the main entry point of the app. When the app is launched, the

Mainclass contains the very first method that is run. - AppDelegate.cs contains the

AppDelegateclass that is responsible for listening to events from the operating system. - Info.plist contains app properties such as the application name, icons, etc.

- Entitlements.plist contains the entitlements for the app and allows access to things such as Sandboxing and iCloud support.

- Main.storyboard defines the user interface (Windows and Menus) for an app and lays out the interconnections between Windows via Segues. Storyboards are XML files that contain the definition of views (user interface elements). This file can be created and maintained by Interface Builder inside of Xcode.

- ViewController.cs is the controller for the main window. Controllers will be covered in detail in another article, but for now, a controller can be thought of the main engine of any particular view.

- ViewController.designer.cs contains plumbing code that helps integrate with the main screen's user interface.

The following sections, will take a quick look through some of these files. Later, they will be explored in more detail, but it's a good idea to understand their basics now.

Main.cs

The Main.cs file is very simple. It contains a static Main method which creates a new Xamarin.Mac app instance and passes the name of the class that will handle OS events, which in this case is the AppDelegate class:

AppDelegate.cs

The AppDelegate.cs file contains an AppDelegate class, which is responsible for creating windows and listening to OS events:

This code is probably unfamiliar unless the developer has built an iOS app before, but it's fairly simple.

The DidFinishLaunching method runs after the app has been instantiated, and it's responsible for actually creating the app's window and beginning the process of displaying the view in it.

The WillTerminate method will be called when the user or the system has instantiated a shutdown of the app. The developer should use this method to finalize the app before it quits (such as saving user preferences or window size and location).

ViewController.cs

Cocoa (and by derivation, CocoaTouch) uses what's known as the Model View Controller (MVC) pattern. The ViewController declaration represents the object that controls the actual app window. Generally, for every window created (and for many other things within windows), there is a controller, which is responsible for the window's lifecycle, such as showing it, adding new views (controls) to it, etc.

The ViewController class is the main window's controller. The controller is responsible for the life cycle of the main window. This will be examined in detail later, for now take a quick look at it:

ViewController.Designer.cs

Xamarin Ide Mac Os

The designer file for the Main Window class is initially empty, but it will be automatically populated by Visual Studio for Mac as the user interface is created with Xcode Interface Builder:

Designer files should not be edited directly, as they're automatically managed by Visual Studio for Mac to provide the plumbing code that allows access to controls that have been added to any window or view in the app.

With the Xamarin.Mac app project created and a basic understanding of its components, switch to Xcode to create the user interface using Interface Builder.

Info.plist

The Info.plist file contains information about the Xamarin.Mac app such as its Name and Bundle Identifier:

It also defines the Storyboard that will be used to display the user interface for the Xamarin.Mac app under the Main Interface dropdown. In example above, Main in the dropdown relates to the Main.storyboard in the project's source tree in the Solution Explorer. It also defines the app's icons by specifying the Asset Catalog that contains them (AppIcon in this case).

Entitlements.plist

The app's Entitlements.plist file controls entitlements that the Xamarin.Mac app has such as Sandboxing and iCloud:

For the Hello World example, no entitlements will be required. The next section shows how to use Xcode's Interface Builder to edit the Main.storyboard file and define the Xamarin.Mac app's UI.

Introduction to Xcode and Interface Builder

As part of Xcode, Apple has created a tool called Interface Builder, which allows a developer to create a user interface visually in a designer. Xamarin.Mac integrates fluently with Interface Builder, allowing UI to be created with the same tools as Objective-C users.

To get started, double-click the Main.storyboard file in the Solution Explorer to open it for editing in Xcode and Interface Builder:

This should launch Xcode and look like this screenshot:

Before starting to design the interface, take a quick overview of Xcode to orient with the main features that will be used.

Note

The developer doesn't have to use Xcode and Interface Builder to create the user interface for a Xamarin.Mac app, the UI can be created directly from C# code but that is beyond the scope of this article. For the sake of simplicity, it will be using Interface Builder to create the user interface throughout the rest of this tutorial.

Components of Xcode

When opening a .storyboard file in Xcode from Visual Studio for Mac, it opens with a Project Navigator on the left, the Interface Hierarchy and Interface Editor in the middle, and a Properties & Utilities section on the right:

The following sections take a look at what each of these Xcode features do and how to use them to create the interface for a Xamarin.Mac app.

Project Navigation

When opening a .storyboard file for editing in Xcode, Visual Studio for Mac creates a Xcode Project File in the background to communicate changes between itself and Xcode. Later, when the developer switches back to Visual Studio for Mac from Xcode, any changes made to this project are synchronized with the Xamarin.Mac project by Visual Studio for Mac.

The Project Navigation section allows the developer to navigate between all of the files that make up this shim Xcode project. Typically, they will only be interested in the .storyboard files in this list such as Main.storyboard.

Interface Hierarchy

The Interface Hierarchy section allows the developer to easily access several key properties of the user interface such as its Placeholders and main Window. This section can be used to access the individual elements (views) that make up the user interface and to adjust the way they are nested by dragging them around within the hierarchy.

Interface Editor

The Interface Editor section provides the surface on which the user interface is graphically laid out. Drag elements from the Library section of the Properties & Utilities section to create the design. As user interface elements (views) are added to the design surface, they will be added to the Interface Hierarchy section in the order that they appear in the Interface Editor.

Properties & Utilities

The Properties & Utilities section is divided into two main sections, Properties (also called Inspectors) and the Library:

Initially this section is almost empty, however if the developer selects an element in the Interface Editor or Interface Hierarchy, the Properties section will be populated with information about the given element and properties that they can adjust.

Within the Properties section, there are eight different Inspector Tabs, as shown in the following illustration:

Properties & Utility Types

From left-to-right, these tabs are:

- File Inspector – The File Inspector shows file information, such as the file name and location of the Xib file that is being edited.

- Quick Help – The Quick Help tab provides contextual help based on what is selected in Xcode.

- Identity Inspector – The Identity Inspector provides information about the selected control/view.

- Attributes Inspector – The Attributes Inspector allows the developer to customize various attributes of the selected control/view.

- Size Inspector – The Size Inspector allows the developer to control the size and resizing behavior of the selected control/view.

- Connections Inspector – The Connections Inspector shows the Outlet and Action connections of the selected controls. Outlets and Actions will be discussed in detail below.

- Bindings Inspector – The Bindings Inspector allows the developer to configure controls so that their values are automatically bound to data models.

- View Effects Inspector – The View Effects Inspector allows the developer to specify effects on the controls, such as animations.

Use the Library section to find controls and objects to place into the designer to graphically build the user interface:

Creating the Interface

With the basics of the Xcode IDE and Interface Builder covered, the developer can create the user interface for the main view.

Follow these steps to use Interface Builder:

In Xcode, drag a Push Button from the Library Section:

Drop the button onto the View (under the Window Controller) in the Interface Editor:

Click on the Title property in the Attribute Inspector and change the button's title to Click Me:

Drag a Label from the Library Section:

Drop the label onto the Window beside the button in the Interface Editor:

Grab the right handle on the label and drag it until it is near the edge of the window:

Select the Button just added in the Interface Editor, and click the Constraints Editor icon at the bottom of the window:

At the top of the editor, click the Red I-Beams at the top and left. As the window is resized, this will keep the button in the same location at the top left corner of the screen.

Next, check the Height and Width boxes and use the default sizes. This keeps the button at the same size when the window resizes.

Click the Add 4 Constraints button to add the constraints and close the editor.

Select the label and click the Constraints Editor icon again:

By clicking Red I-Beams at the top, right and left of the Constraints Editor, tells the label to be stuck to its given X and Y locations and to grow and shrink as the window is resized in the running application.

Again, check the Height box and use the default size, then click the Add 4 Constraints Open dwg mac. button to add the constraints and close the editor.

Save the changes to the user interface.

While resizing and moving controls around, notice that Interface Builder gives helpful snap hints that are based on macOS Human Interface Guidelines. These guidelines will help the developer to create high quality apps that will have a familiar look and feel for Mac users.

Look in the Interface Hierarchy section to see how the layout and hierarchy of the elements that make up the user interface are shown:

From here the developer can select items to edit or drag to reorder UI elements if needed. For example, if a UI element was being covered by another element, they could drag it to the bottom of the list to make it the top-most item on the window.

With the user interface created, the developer will need to expose the UI items so that Xamarin.Mac can access and interact with them in C# code. The next section, Outlets and Actions, shows how to do this.

Outlets and Actions

So what are Outlets and Actions? In traditional .NET user interface programming, a control in the user interface is automatically exposed as a property when it's added. Things work differently in Mac, simply adding a control to a view doesn't make it accessible to code. The developer must explicitly expose the UI element to code. In order do this, Apple provides two options:

- Outlets – Outlets are analogous to properties. If the developer wires up a control to an Outlet, it's exposed to the code via a property, so they can do things like attach event handlers, call methods on it, etc.

- Actions – Actions are analogous to the command pattern in WPF. For example, when an Action is performed on a control, say a button click, the control will automatically call a method in the code. Actions are powerful and convenient because the developer can wire up many controls to the same Action.

In Xcode, Outlets and Actions are added directly in code via Control-dragging. More specifically, this means that to create an Outlet or Action, the developer will choose a control element to add an Outlet or Action to, hold down the Control key on the keyboard, and drag that control directly into the code.

For Xamarin.Mac developers, this means that the developer will drag into the Objective-C stub files that correspond to the C# file where they want to create the Outlet or Action. Visual Studio for Mac created a file called ViewController.h as part of the shim Xcode Project it generated to use Interface Builder:

Xamarin Demand

This stub .h file mirrors the ViewController.designer.cs that is automatically added to a Xamarin.Mac project when a new NSWindow is created. This file will be used to synchronize the changes made by Interface Builder and is where the Outlets and Actions are created so that UI elements are exposed to C# code.

Adding an Outlet

With a basic understanding of what Outlets and Actions are, create an Outlet to expose the Label created to our C# code.

Do the following:

In Xcode at the far right top-hand corner of the screen, click the Double Circle button to open the Assistant Editor:

The Xcode will switch to a split-view mode with the Interface Editor on one side and a Code Editor on the other.

Notice that Xcode has automatically picked the ViewController.m file in the Code Editor, which is incorrect. From the discussion on what Outlets and Actions are above, the developer will need to have the ViewController.h selected.

At the top of the Code Editor click on the Automatic Link and select the

ViewController.hfile:Xcode should now have the correct file selected:

The last step was very important!: if you didn't have the correct file selected, you won't be able to create Outlets and Actions, or they will be exposed to the wrong class in C#!

In the Interface Editor, hold down the Control key on the keyboard and click-drag the label created above onto the code editor just below the

@interface ViewController : NSViewController {}code:A dialog box will be displayed. Leave the Connection set to Outlet and enter

ClickedLabelfor the Name:Click the Connect button to create the Outlet:

Save the changes to the file.

Adding an Action

Next, expose the button to C# code. Just like the Label above, the developer could wire the button up to an Outlet. Since we only want to respond to the button being clicked, use an Action instead.

Do the following:

Ensure that Xcode is still in the Assistant Editor and the ViewController.h file is visible in the Code Editor.

In the Interface Editor, hold down the Control key on the keyboard and click-drag the button created above onto the code editor just below the

@property (assign) IBOutlet NSTextField *ClickedLabel;code:Change the Connection type to Action:

Enter

ClickedButtonas the Name:Click the Connect button to create Action:

Save the changes to the file.

With the user interface wired-up and exposed to C# code, switch back to Visual Studio for Mac and let it synchronize the changes made in Xcode and Interface Builder.

Note

It probably took a long time to create the user interface and Outlets and Actions for this first app, and it may seem like a lot of work, but a lot of new concepts were introduced and a lot of time was spent covering new ground. After practicing for a while and working with Interface Builder, this interface and all its Outlets and Actions can be created in just a minute or two.

Synchronizing Changes with Xcode

When the developer switches back to Visual Studio for Mac from Xcode, any changes that they have made in Xcode will automatically be synchronized with the Xamarin.Mac project.

Select the ViewController.designer.cs in the Solution Explorer to see how the Outlet and Action have been wired up in the C# code:

Notice how the two definitions in the ViewController.designer.cs file:

Line up with the definitions in the ViewController.h file in Xcode:

Visual Studio for Mac listens for changes to the .h file, and then automatically synchronizes those changes in the respective .designer.cs file to expose them to the app. Notice that ViewController.designer.cs is a partial class, so that Visual Studio for Mac doesn't have to modify ViewController.cs which would overwrite any changes that the developer has made to the class.

What mac do i have. Normally, the developer will never need to open the ViewController.designer.cs, it was presented here for educational purposes only.

Note

In most situations, Visual Studio for Mac will automatically see any changes made in Xcode and sync them to the Xamarin.Mac project. In the off occurrence that synchronization doesn't automatically happen, switch back to Xcode and then back to Visual Studio for Mac again. This will normally kick off a synchronization cycle.

Writing the Code

With the user interface created and its UI elements exposed to code via Outlets and Actions, we are finally ready to write the code to bring the program to life.

For this sample app, every time the first button is clicked, the label will be updated to show how many times the button has been clicked. To accomplish this, open the ViewController.cs file for editing by double-clicking it in the Solution Explorer:

First, create a class-level variable in the ViewController class to track the number of clicks that have happened. Edit the class definition and make it look like the following:

Next, in the same class (ViewController), override the ViewDidLoad method and add some code to set the initial message for the label:

Use ViewDidLoad, instead of another method such as Initialize, because ViewDidLoad is called after the OShas loaded and instantiated the user interface from the .storyboard file. If the developer tried to access the label control before the .storyboard file has been fully loaded and instantiated, they would get a NullReferenceException error because the label control would not exist yet.

Next, add the code to respond to the user clicking the button. Add the following partial method to the ViewController class:

This code attaches to the Action created in Xcode and Interface Builder and will be called any time the user clicks the button.

Testing the Application

It's time to build and run the app to make sure it runs as expected. The developer can build and run all in one step, or they can build it without running it.

Whenever an app is built, the developer can choose what kind of build they want:

- Debug – A debug build is compiled into an .app (application) file with a bunch of extra metadata that allows the developer to debug what's happening while the app is running.

- Release – A release build also creates an .app file, but it doesn't include debug information, so it's smaller and executes faster.

The developer can select the type of build from the Configuration Selector at the upper left-hand corner of the Visual Studio for Mac screen:

Building the Application

In the case of this example, we just want a debug build, so ensure that Debug is selected. Build the app first by either pressing ⌘B, or from the Build menu, choose Build All.

If there weren't any errors, a Build Succeeded message will be displayed in Visual Studio for Mac's status bar. If there were errors, review the project and make sure that the steps above have been followed correctly. Start by confirming that the code (both in Xcode and in Visual Studio for Mac) matches the code in the tutorial.

Running the Application

There are three ways to run the app:

- Press ⌘+Enter.

- From the Run menu, choose Debug.

- Click the Play button in the Visual Studio for Mac toolbar (just above the Solution Explorer).

The app will build (if it hasn't been built already), start in debug mode and display its main interface window:

If the button is clicked a few times, the label should be updated with the count:

Where to Next

With the basics of working with a Xamarin.Mac application down, take a look at the following documents to get a deeper understanding:

- Introduction to Storyboards - This article provides an introduction to working with Storyboards in a Xamarin.Mac app. It covers creating and maintaining the app's UI using storyboards and Xcode's Interface Builder.

- Windows - This article covers working with Windows and Panels in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Windows and Panels in Xcode and Interface builder, loading Windows and Panels from .xib files, using Windows and responding to Windows in C# code.

- Dialogs - This article covers working with Dialogs and Modal Windows in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Modal Windows in Xcode and Interface builder, working with standard dialogs, displaying and responding to Windows in C# code.

- Alerts - This article covers working with Alerts in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and displaying Alerts from C# code and responding to Alerts.

- Menus - Menus are used in various parts of a Mac application's user interface; from the application's main menu at the top of the screen to pop up and contextual menus that can appear anywhere in a window. Menus are an integral part of a Mac application's user experience. This article covers working with Cocoa Menus in a Xamarin.Mac application.

- Toolbars - This article covers working with Toolbars in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining. Toolbars in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Toolbar Items to code using Outlets and Actions, enabling and disabling Toolbar Items and finally responding to Toolbar Items in C# code.

- Table Views - This article covers working with Table Views in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Table Views in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Table View Items to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Table Items and finally responding to Table View Items in C# code.

- Outline Views - This article covers working with Outline Views in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Outline Views in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Outline View Items to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Outline Items and finally responding to Outline View Items in C# code.

- Source Lists - This article covers working with Source Lists in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Source Lists in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Source Lists Items to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Source List Items and finally responding to Source List Items in C# code.

- Collection Views - This article covers working with Collection Views in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining Collection Views in Xcode and Interface builder, how to expose the Collection View elements to code using Outlets and Actions, populating Collection Views and finally responding to Collection Views in C# code.

- Working with Images - This article covers working with Images and Icons in a Xamarin.Mac application. It covers creating and maintaining the images needed to create an app's Icon and using Images in both C# code and Xcode's Interface Builder.

The Mac Samples Gallery contains ready-to-use code examples to help learn Xamarin.Mac.

One complete Xamarin.Mac app that includes many of the features a user would expect to find in a typical Mac application is the SourceWriter Sample App. SourceWriter is a simple source code editor that provides support for code completion and simple syntax highlighting.

The SourceWriter code has been fully commented and, where available, links have been provided from key technologies or methods to relevant information in the Xamarin.Mac documentation.

Summary

This article covered the basics of a standard Xamarin.Mac app. It covered creating a new app in Visual Studio for Mac, designing the user interface in Xcode and Interface Builder, exposing UI elements to C# code using Outlets and Actions, adding code to work with the UI elements and finally, building and testing a Xamarin.Mac app.

Related Links

-->The Xamarin platform consists of a number of elements that allow you todevelop applications for iOS and Android:

- C# language – Allows you to use a familiar syntax and sophisticated features like Generics, LINQ and the Parallel Task Library.

- Mono .NET framework – Provides a cross-platform implementation of the extensive features in Microsoft's .NET framework.

- Compiler – Depending on the platform, produces a native app (eg. iOS) or an integrated .NET application and runtime (eg. Android). The compiler also performs many optimizations for mobile deployment such as linking away un-used code.

- IDE tools – The Visual Studio on Mac and Windows allows you to create, build, and deploy Xamarin projects.

In addition, because the underlying language is C# with the .NET framework,projects can be structured to share code that can also be deployed to WindowsPhone.

Under the Hood

Although Xamarin allows you to write apps in C#, and share the same codeacross multiple platforms, the actual implementation on each system is verydifferent.

Compilation

The C# source makes its way into a native app in very different ways on eachplatform:

- iOS – C# is ahead-of-time (AOT) compiled to ARM assembly language. The .NET framework is included, with unused classes being stripped out during linking to reduce the application size. Apple does not allow runtime code generation on iOS, so some language features are not available (see Xamarin.iOS Limitations ).

- Android – C# is compiled to IL and packaged with MonoVM + JIT'ing. Unused classes in the framework are stripped out during linking. The application runs side-by-side with Java/ART (Android runtime) and interacts with the native types via JNI (see Xamarin.Android Limitations ).

- Windows – C# is compiled to IL and executed by the built-in runtime, and does not require Xamarin tools. Designing Windows applications following Xamarin's guidance makes it simpler to re-use the code on iOS and Android.Note that the Universal Windows Platform also has a .NET Native option which behaves similarly to Xamarin.iOS' AOT compilation.

Xamarin Ide Mac Os

The linker documentation for Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android provides moreinformation about this part of the compilation process.

Runtime 'compilation' – generating code dynamically with System.Reflection.Emit – should be avoided.

Apple's kernel prevents dynamic code generation on iOS devices, therefore emitting code on-the-fly will not work in Xamarin.iOS. Likewise, the Dynamic Language Runtime features cannot be used with Xamarin tools.

Some reflection features do work (eg. MonoTouch.Dialog uses it for the Reflection API), just not code generation.

Platform SDK Access

Xamarin makes the features provided by the platform-specific SDK easily accessible with familiar C# syntax:

- iOS – Xamarin.iOS exposes Apple's CocoaTouch SDK frameworks as namespaces that you can reference from C#. For example the UIKit framework that contains all the user interface controls can be included with a simple

using UIKit;statement. - Android – Xamarin.Android exposes Google's Android SDK as namespaces, so you can reference any part of the supported SDK with a using statement, such as

using Android.Views;to access the user interface controls. - Windows – Windows apps are built using Visual Studio on Windows. Project types include Windows Forms, WPF, WinRT, and the Universal Windows Platform (UWP).

Seamless Integration for Developers

The beauty of Xamarin is that despite the differences under the hood,Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android (coupled with Microsoft's Windows SDKs)offer a seamless experience for writing C# code that can be re-used across allthree platforms.

Business logic, database usage, network access, and other common functions canbe written once and re-used on each platform, providing a foundation forplatform-specific user interfaces that look and perform as native applications.

Integrated Development Environment (IDE) Availability

Xamarin development can be done in Visual Studio on either Mac or Windows. TheIDE you choose will be determined by the platforms you wish to target.

Because Windows apps canonly be developed on Windows, to build for iOS, Android, and Windows requiresVisual Studio for Windows. However it's possible to share projects and filesbetween Windows and Mac computers, so iOS and Android apps can be built ona Mac and shared code could later be added to a Windows project.

The development requirements for each platform are discussed in more detailin the Requirement guide.

iOS

Developing iOS applications requires a Mac computer, running macOS. You can also use Visual Studio to write and deploy iOS applications with Xamarin in Visual Studio. However, a Mac is still needed for build and licensing purposes.

Apple's Xcode IDE must be installed to provide the compiler and simulatorfor testing. You can test on your own devices for free,but to build applications for distribution (eg. the App Store)you must join Apple's Developer Program ($99 USD per year). Each time yousubmit or update an application, it must be reviewed and approved by Apple beforeit is made available for customers to download.

Code is written with the Visual Studio IDEand screen layouts can be builtprogrammatically or edited with Xamarin's iOS Designer in either IDE.

Refer to the Xamarin.iOS Installation Guide fordetailed instructions on getting set up.

Android

Android application development requires the Java and Android SDKs to beinstalled. These provide the compiler, emulator and other tools required forbuilding, deployment and testing. Java, Google's Android SDK and Xamarin'stools can all be installed and run on Windows and macOS. The following configurationsare recommended:

- Windows 10 with Visual Studio 2019

- macOS Mojave (10.11+) with Visual Studio 2019 for Mac

Xamarin provides a unified installer that will configure your system with thepre-requisite Java, Android and Xamarin tools (including a visual designer forscreen layouts). Refer to the Xamarin.Android Installation Guide for detailed instructions.

You can build and test applications on a real device without any license fromGoogle, however to distribute your application through a store (such as GooglePlay, Amazon or Barnes & Noble) a registration fee may be payable to theoperator. Google Play will publish your app instantly, while the other storeshave an approval process similar to Apple's.

Windows

Windows apps (WinForms, WPF, or UWP) are built with Visual Studio. They do not use Xamarin directly. However, C# code canbe shared across Windows, iOS and Android.Visit Microsoft's Dev Center to learn about the tools required for Windows development.

Creating the User Interface (UI)

A key benefit of using Xamarin is that the application user interface usesnative controls on each platform, creating apps that are indistinguishable from anapplication written in Objective-C or Java (for iOS and Androidrespectively).

When building screens in your app, you can either lay out the controls incode or create complete screens using the design tools available for eachplatform.

Create Controls Programmatically

Each platform allows user interface controls to be added to a screen usingcode. This can be very time-consuming as it can be difficult to visualize thefinished design when hard-coding pixel coordinates for control positions andsizes.

Programmatically creating controls does have benefits though, particularly oniOS for building views that resize or render differently across the iPhone andiPad screen sizes.

Visual Designer

Each platform has a different method for visually laying out screens:

- iOS – Xamarin's iOS Designer facilitates building Views using drag-and-drop functionality and property fields. Collectively these Views make up a Storyboard, and can be accessed in the .Storyboard file that is included in your project.

- Android – Xamarin provides an Android drag-and-drop UI designer for Visual Studio. Android screen layouts are saved as .AXML files when using Xamarin tools.

- Windows – Microsoft provides a drag-and-drop UI designer in Visual Studio and Blend. The screen layouts are stored as .XAML files.

These screenshots show the visual screen designers available on eachplatform:

In all cases the elements that you create visually can be referenced in yourcode.

User Interface Considerations

A key benefit of using Xamarin to build cross platform applications is thatthey can take advantage of native UI toolkits to present a familiar interface tothe user. The UI will also perform as fast as any other native application.

Some UI metaphors work across multiple platforms (for example, all threeplatforms use a similar scrolling-list control) but in order for yourapplication to ‘feel' right the UI should take advantage ofplatform-specific user interface elements when appropriate. Examples ofplatform-specific UI metaphors include:

- iOS – hierarchical navigation with soft back button, tabs on the bottom of the screen.

- Android – hardware/system-software back button, action menu, tabs on the top of the screen.

- Windows – Windows apps can run on desktops, tablets (such as Microsoft Surface) and phones. Windows 10 devices may have hardware back button and live tiles, for example.

It is recommended that you read the design guidelines relevant to theplatforms you are targeting:

- iOS – Apple's Human Interface Guidelines

- Android – Google's User Interface Guidelines

- Windows – User Experience Design Guidelines for Windows

Library and Code Re-Use

Xamarin Ide Mac Download

The Xamarin platform allows re-use of existing C# code across all platformsas well as the integration of libraries written natively for each platform.

C# Source and Libraries

Because Xamarin products use C# and the .NET framework, lots of existingsource code (both open source and in-house projects) can be re-used in Xamarin.iOSor Xamarin.Android projects. Often the source can simply be added to a Xamarinsolution and it will work immediately. If an unsupported .NET framework featurehas been used, some tweaks may be required.

Xamarin Itemcontrol

Examples of C# source that can be used in Xamarin.iOS or Xamarin.Androidinclude: SQLite-NET, NewtonSoft.JSON and SharpZipLib.

Objective-C Bindings + Binding Projects

Xamarin provides a tool called btouch that helps create bindingsthat allow Objective-C libraries to be used in Xamarin.iOS projects. Refer to the Binding Objective-C Types documentation for details on how this is done.

Examples of Objective-C libraries that can be used in Xamarin.iOS include: RedLaserbarcode scanning, Google Analytics and PayPal integration. Open-source Xamarin.iOSbindings are available on github.

.jar Bindings + Binding Projects

Xamarin supports using existing Java libraries in Xamarin.Android. Refer tothe Binding a Java Library documentation for details on how to use a .JAR filefrom Xamarin.Android.

Open-source Xamarin.Android bindings are available on github.

C via PInvoke

'Platform Invoke' technology (P/Invoke) allows managed code (C#) to callmethods in native libraries as well as support for native libraries to call backinto managed code.

For example, the SQLite-NET library uses statements like this:

This binds to the native C-language SQLite implementation in iOS and Android.Developers familiar with an existing C API can construct a set of C# classes tomap to the native API and utilize the existing platform code. There isdocumentation for linking native libraries in Xamarin.iOS, similar principles apply to Xamarin.Android.

C++ via CppSharp

Miguel explains CXXI (now called CppSharp) on his blog. Analternative to binding to a C++ library directly is to create a C wrapper andbind to that via P/Invoke.